Justin C. Key’s “The Perfection of Theresa Watkins” is a skillful speculative exploration of the intersection of race, mental illness, and the American prison system.

Darius and Theresa Watkins confronted death once as fellow cancer survivors. Their lives are full and productive, their love a shield against Darius’s bouts of anxiety and Theresa’s occasional flare-ups. Yet when tragedy strikes, Darius will try everything to save his wife…even against his fears that she may have transformed into an entirely different person—literally.

Perfect. Everything had to be perfect. The living room couch’s relation to our centrally framed wedding picture. The entertainment center’s arrangement of rimmed diplomas, captured memories, and diverse snow globes. The half-filled kitchen trashcan, scant dishes in the sink, and a bathroom between cleanings made for a homely smell, one that said we did when we “could,” and that “could” came less often than we’d liked.

If things weren’t perfect, I’d lose her again.

The water I poured to ease down the Xanax sloshed out of the cup, onto the counter, and dribbled cold onto my socks. I hated medication, but Resurrection, Inc. advised against the electronic limbic treatments that usually eliminated my attacks all together. They’d prescribed me a short-acting sedative to take “as needed” until things at home resembled normal. Despite warnings of the medication’s addictive properties, I found myself taking more and more lately.

My arm muscles were trembling tuning forks as I twisted off the medicine cap and popped a pill. Then I counted.

Onetwothree, onetwothree, one, two, three, one…two…three. My heart slowed to its background pace. Thoughts reformed from fragmented worries.

And then, a voice: “It took me long enough.”

I straightened, banged my head on the edge of the pantry door, and saw stars. One pair amongst them shone bright. One I’d feared I’d never see again.

Buy the Book

The Perfection of Theresa Watkins

A white woman stood under the dining room lights. I had spent the morning agonizing on this first moment, formulating the perfect greeting and gestures and phrases fitting for our happily ever after. Now my dead wife was here, and I stood clutching my head, my mouth leaking water. What’s more, I was unprepared to hide the shock. She looked like a distant relative of the wild-haired prisoner from the donor pictures. She looked nothing like my wife.

Except for the eyes.

She spread her arms. “I’m white, Darius. Only in America.” The voice was wrong; Theresa’s had been lower. “Ian’ll have a field day with this.”

“Life lasts a lifetime, our love lasts forever.” The rehearsed phrase had sounded a lot better in front of the mirror that morning.

She laughed. My skin went down a size. This wasn’t going well. I turned to busy my hands with another glass of water.

“I’ve missed the shit out of you,” she said, suddenly beside me. Her mouth fell over mine. The lips were thin. Her taste was sweet, different than what I was used to; I had kissed the same pair of lips for almost a decade.

I pulled away and touched her face. The skin was rough and pink beneath the makeup, where Theresa’s had been smooth umber.

“Do you see me?” she asked. “I see you.”

“You have her eyes,” I said. “Your eyes, I mean.”

Long and thin with sunken cheeks, she had the face of a woman who had been through a few things, but a long time ago. This new face was without menace or malevolence—Resurrection, Inc. had gone through great lengths to reverse decades of incarceration—yet somehow darker in its whiteness than Theresa’s had ever been. Life-etched shadows lingered like erased pencil markings.

Whether I knew it then or not, her body had its own memories.

Nine years before Resurrection

My first panic attack came the same day I met my wife. As Ian Cole’s car pulled up to New York Presbyterian Hospital, a hand—perhaps God’s—gripped my heart as I gripped the door handle. What if my body couldn’t take this round of chemo? What if a clot formed in the line and went straight to my brain? Every muscle in my body twitched to run.

“Bruh,” Ian said, his hand on my shoulder. “Your forehead shiny as hell right now. You good? Should I call Jerry?”

“I’m fine,” I said as I opened the door. He and Jerry Brown, old college roommates turned business partners, helped me through treatments the best they knew how. Ian made sure I made my appointments, and that life still had laughter. Jerry the Christian visited to pray over me. He continued silently even after I told him to stop, and I resented him for it. The last thing I wanted was help from Jerry the Psychiatrist. “See you in two?”

I was out before he could answer. In the hospital lobby, I busied my hands under the sanitizer dispenser. The bubbles popped red; my own fingernails had drawn blood. I wiped them clean and hurried to the oncology floor.

In months I went from being a young computer engineer with a budding 401(k), stock options for three different tech start-ups, my own business, and a vibrant online dating profile to a shadow of a man voluntarily pumping poison into his veins. The chemo had eaten everything else—my hair, my energy, my digestive system, my hope, and my faith—why not feed it this new sensation, too? I willed myself to the treatment chair; the toxins mixed with my blood while I was still on the verge of breakdown. It ate at me—all of me—and I found sleep.

I dreamed chemo-torn dreams, my weathered mind left to reconstruct splinters of cognition. I was back in my childhood bedroom, only my twin-sized mattress had become a deathbed. My legs dangled over the edge; my feet scritch-scratched, scritch-scratched against the wood as I trembled from the drugs.

My dead mother tended to me. Bits of blackened flesh dropped from the rotting hole in her neck into my tea. She somehow saw my fear with her cold eyes, and began to sing. The whites of her spinal cord were visible through the shreds of her throat. More bits fell into the cup.

And then, I felt God’s hand on mine. I tried to pull away. Didn’t He know we were done?

My dreams broke under His touch. I looked down, curious to see the Hand of God. Thin, spotted skin stretched pale over straining knuckles. The slender fingers were strangely delicate. My laughter came out as a painful cough. God was Black. God was Woman.

I looked up, ready, and saw not God, but instead someone broken like me. Her eyes and mouth were tight lines under a domed head capped with a purple polka dot scarf. Dark patches stained mahogany skin that lay lazy over her skull. Orange lines shuttled treatment from hanging bags into her swollen arm. She wasn’t the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.

She woke some time later to me watching her. After a brief, orienting smile, she sat up and pulled her hand into her lap.

“You’re not going to get weird on me, now are you?” She spoke slowly, as if parts of her were still dreaming.

“You were holding my hand,” I said.

“I always find the smart ones.” She pointed to herself. “Theresa, ovarian cancer. What you got?”

“Uh, Darius. Lymphoma. I’ve got three more sessions.”

She nodded, closed her eyes, and laid her head back against her seat. I thought sleep had reclaimed her when she spoke again. “Same, more or less. See you Thursday?”

No, I didn’t think so. The sessions had taken their toll. Even with them, my chances were slim. The quick flick of a knife across my wrist would offer a much cleaner death. A lot could happen before Thursday.

But I didn’t tell her that. “Yes. Definitely,” I said.

And I did. That Thursday and many times after.

That was the worst of the chemo, and in some ways the best. Remission, like our relationship, had its expected highs and lows. I often thought of chemotherapy as a kind of first death. The hopelessness, the fear, the exhaustion, spiraling down to a forfeit that finally ushered us into a second life of recovery and relationship.

We had found love in poison. We had found life in death.

We sat facing each other on the living room couch, Theresa’s right foot tucked underneath her. She’d spent the last hour retelling what she remembered of how we first met. Resurrection, Inc. had adamantly stressed the importance of these drills to further cement her memories. I relived many of them as she did, only correcting small details, (the year was off by one, for example) and filling in a few blanks. Besides the occasional confirmatory eye contact, her gaze was off interrogating the past. In her words I saw Theresa’s original face, so detailed in its color that focusing on the woman now in front of me was physically jolting. Her new white skin competed with memory, pushing out the brown, the imperfect blemishes, the resilience within the pain of cancer that had initially called my spirit to hers. I fought for hold. My heart thrashed against my chest and lungs. The walls breathed out and shrank in like the tide.

Theresa touched my hand. I calmed in her eyes.

Thank God for the eyes.

“This is hard,” she said. “I know.”

“They offered to let me remember you this way.” I pulled out my remnant card. “I still can.”

“I want you to remember me like I remember me.”

I reached over to brush away an intrusive strand of hair and found myself trying to curl it with the tip of my finger. Theresa placed her hand over mine. Her face flushed in a way that wouldn’t have been possible before.

“I hate it, too,” she said. “They tried—Lord knows they tried—but the curls wouldn’t hold. I looked like a weeping willow. Not cute. Brain transplant? Piece of cake. Trans-racial hair? Who do you think we are? Miracle workers?”

We shared a laugh. It felt good.

“I almost broke up with you when we were both out of the woods,” Theresa said, still smiling.

“Yeah?” This was news to me. I considered telling her to save the story for another time. Her brain was still unraveling itself. How would I know if the memory was correctly linked? Instead, I said, “Why?”

“We met dying. It didn’t seem like a smart foundation. You never thought of it that way?”

I hadn’t. In the weeks before meeting her, my nights were spent in a bathroom reeking of vomit, a chef’s knife hovering over my wrist, waiting for the courage to end it all, to take back control. After Theresa, when I touched the handle I could think only of seeing Thursday. The chemo had saved my body, but Theresa had saved my life.

The doorbell rang. Thank God. “That’s the food,” I said.

“I’ll get it,” Theresa said, rising. “I need to stretch my legs every few minutes anyway.” When she saw my expression, she added. “I have to keep the neurons firing.”

“You got to sleep, though, don’t you?”

“Didn’t they tell you? I don’t sleep.”

“Really?”

“Joking, babe,” she threw over her shoulder. Her hair went the opposite direction whenever she moved. It was distracting. “Sleep’s the easy part. That’s where all the magic happens. At least, that’s what they told me.”

I admired Resurrection’s work. In remission, fitness had become as much a priority to Theresa as maintaining her monthly doctor visits. Despite the company’s assurances, I’d expected the worst from her donor body. Years of incarceration doesn’t look good on anybody. But a month of training both mind and body between neural implantation and family presentation had given her toned legs with little blemish and buttocks that sat high atop her thighs. She even had the same rim of belly fat she called “love handles” and I called “sexy.” Nearly caught up in the illusion, I fully realized the magnitude of what Resurrection had accomplished. They’d cheated the grave. Fear grazed my heart.

I went to clear the dining room chairs and table of the clutter I’d artificially planted, and began to set for dinner. When I came back out of the kitchen with our guest plates, I frowned. Theresa was sitting in the wrong place. I saw the problem and plucked a piece of mail that had fallen in the seat directly across from her. The correct seat.

“If I remember this right, this smell is a good smell,” she said as she pulled out cartons of food from a brown bag.

“Sorry for the mess,” I said, waving the piece of mail. “You can sit here.”

“I’m fine, it’s not a problem. Champignon makes catfish?”

“They do now, yes.” I sat, then stood. My fingers twitched against my thigh. “You sure you don’t want to switch? Facing the kitchen means you see all the dirty dishes and that means bad mood bears…remember?”

“Of course I remember. The kitchen’s clean, though. So no worries, right?”

“Right. Sure. It’s just…you sit here, and I sit there. You know what? Nevermind, it’s not important.”

Theresa rose. “Trade with me,” she said.

“Really, it’s fine.”

“I’m serious. Looking into the kitchen is depressing. Reminds me that I need to learn to cook all over again.”

My thumb nail picked at my pinky knuckle. Had I already taken my allotted pill for today? Yes, earlier. Before she came.

I smiled. “Perfect. Let’s eat.”

“Where did I propose?” I asked. We lay in bed, continuing the talks that were supposed to be like exercise for a resettling brain.

“Under a willow tree in…Marcus Garvey…?”

“Central Park. It’s okay.”

“Shit, yes, Central. You were such a hopeless romantic. Didn’t you say you wanted us to be buried under that tree?”

“I was high on love. What can I say? Okay, next question. First kiss?”

But Theresa was staring off to the side, her smile barely hanging on. Her eyes darted within their sockets; her mouth grew thin.

“Theresa.”

“Hmm?”

“You looked…distracted. You okay?”

“Yeah, I was just thinking about something.”

“No voices?”

She smiled. “No voices.”

Soft vibrations through the sheets. Theresa frowned, reached under her pillow, and pulled out her phone. She stared at the screen for what seemed like a long time.

“Everything good?” Resurrection, Inc. had issued her a private, restricted line for her probationary transition period.

“Yeah. Just a reminder of my next appointment.” She slid the phone back under the pillow. “What else you got?”

“What was it like?”

“What was what like?”

“Dying.”

“Ah, that,” she said. Her expression went serious. Her lips scrunched up towards her nose. The arrangement nipped at a corner of my mind until I recognized it as a pirated version of the old Theresa’s thinking face. She probably didn’t even notice she was doing it; her muscles simply weren’t all yet in sync with the neural networks controlling them. I imagined thoughts wandering her brain, bumping into things like someone taking a midnight trip to the bathroom in a new home.

“Please,” Theresa said. She’d stopped me from pushing the right corner of her mouth just a little bit higher, where it should be. “Be patient with me.”

I tucked my hand away. “What was it like?” I said.

“Remember when we went bungee jumping in Ecuador? It’s like that, but slower. A lot slower. I went down and down and down until I couldn’t go down anymore. Then I was coming back up.”

“Immediately?”

“No. Not immediately. There was some time. A couple hours, maybe?”

“A week. It took a whole week to get you back in a body.”

“Wow. I mean, I had to be somewhere, right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Somewhere.”

Her staring eyes bled over my dreams, drowning them. I rose to consciousness. The night was soundless and dark. Theresa’s gaze was so much a part of my past, from moments of love to rage to lust, that I felt it even in sleep.

Thank God for the eyes. I thanked Him who no longer existed for me, as I had thanked Him when I first knew—really knew—Theresa was coming home. Sometimes it was just easier to have someone to thank.

Thank God for the eyes.

I should have sat up to share this moment with her, whatever this moment was. I should have asked if she was all right. I should have found out why the hell she was watching me in the middle of the night.

Instead, I pushed my face into the pillows to recapture sleep before it scurried too far away.

Thank God for the eyes.

Seven years before Resurrection

“It’s blasphemy,” Theresa said. She rolled up the plastic from our new coffee maker, shoved it in the trashcan, and snatched the Resurrection, Inc. pamphlet from my hand. We’d just moved in together in the Upper West Side.

“What’s the harm in meeting with them? See what they’re all about?”

“I already know what they’re all about. It says so right here. ‘Be the master of your fate. Be the Captain of your soul.’ God is the captain of my soul.”

“I’ll make an appointment,” I said. “Just a consult. And if you don’t like it, we don’t have to do it. At all.”

She leaned against the kitchen counter and sighed, long and heavy, as her eyes scanned the sheet of paper. I saw my chance.

“I don’t want to lose you,” I said. “I don’t want to lose us.”

Resurrection, Inc. was located on the twelfth floor of a downtown office building. A tall, thin man with a pin-striped suit, wavy black hair, and a metallic smile greeted us outside the elevator. Theresa burst into laughter when she saw him.

“Ian?” she said, wiping her eyes. “You run this?”

“I’ll take that as a compliment. You were really going to leave all the explaining to me, huh, Darius?”

“I thought you were out today?” I said.

“I cleared my schedule. Did D tell you he helped invent this tech?”

“‘Helped invent’ is a big stretch,” I said.

“No.” Theresa’s laughter had come and gone like a mid-summer’s rain. “I had no idea, actually. You told me you were part of a tech start-up.”

“I was,” I said. “Neurotech. Always good to see you, Ian. You mind putting on your business face and showing us around?”

Resurrection’s office was a smaller version of the psychiatry suites I had come to know well. Books lined the shelves. The walls popped with color. Besides the corner computer hooked up to a long, silver-and-black robotic arm with eager fingers, it felt more like visiting someone’s home. Theresa looked around as if the place smelled foul.

Ian served us green tea as an assistant fitted us with helmets covered with electrodes connected to the computer.

“How is this better than the brain transplants?” I asked after Ian had explained their service. It had been very hard to take Ian’s idea of neuro transplants seriously back when we were managing Continuum. Jerry, Ian, and I had built the life-saving ELT clinic from scratch. When I got cancer and Jerry got saved, Ian partnered with a couple of angel investors desperate to see if wealth could turn into immortality. Resurrection was born. Even then I had paid little attention to the details. Now, there was something about potentially being on the receiving end that riled the curiosity.

“A brain transplant is only the riskiest procedure known to medicine. There’s a fifty percent chance of rejection. Fifty percent. That’s flipping a coin to see whether or not your new body attacks your brain.”

“There’s been some success,” I said.

“In Japan, yes. But no one knows the long-term outcome. And you only have one copy of your brain. If something—anything—goes wrong, lights out. In a perfect world, the outcome would technically, maybe be better. But we live in the real world. You have your remnant card?”

I did. I hesitated, sent Theresa a nervous smile, and took out my keychain. The blue-and-red striped piece of metal looked like a dogtag. My ticket into the ELT clinics, it was on me at all times. Ian slipped it into one of the computer’s sockets.

“And when’s the last time you had ELT?”

“A week ago.”

“Long enough,” Ian said. “Pick up the can.”

“What’s ELT?” Theresa said.

“Electronic limbic treatment,” Ian said, fully ignoring my targeted annoyance. “Continuum was the first to do it, I might add. We created, others stylized.”

“So you’re also a customer?” Theresa said. “What’s next, you’re going to tell me you’re a robot?”

“Well—”

“Shut up, Ian.” I turned to Theresa. “Look, honey, I didn’t want you to freak out. But we—they—do good work. Remember how bad I was?”

“Just go on and pick up the damn thing,” Theresa said.

I concentrated. Nothing happened.

“You’re getting ahead of me,” Ian said. “Pick it up with your hand. Like you normally would.”

I did. The metal was warm. I placed it back.

Ian clacked away at the computer. “Do it again.”

I did. The sliver of movement out of the corner of my eye could have been my imagination, but I knew it wasn’t.

“I don’t need the read-out to tell me your mind’s running,” Ian said. “Talk to me.”

“I was just thinking. When I code, I can make a program on one computer and then use it on any other. They all share the same basic language. Our brains aren’t like that. They’re all different.”

“Ah. But when I look at this can, I see red. You see red.”

“My red may be different from your red.”

“Does it matter, though, if we both agree it’s red? In a sense, we don’t talk to each other, our interpreters do. They take our complex network of unique electrical signals and turn them into a common result. If I thought of the word ‘fruit’ and stimulated the same firing pattern in your brain without the interpreter, you might think of the word ‘meat.’ Or it might not even be a word at all. You might see a certain color, or smell a certain smell.

“The remnant card stores your neural connections. Resurrection stores your interpreter. Together, it’s like packaging a novel with a universal translator.” Ian turned the computer screen towards me. Thousands of lines connected dots in a virtual plane that took the crude shape of a brain. “See, here’s a snapshot of you lifting the can. Here’s a snapshot of the sensory input and output at that time. And here’s the intersection of those two. The Interpreter.”

Lines of code in an unfamiliar language scrolled the screen for five seconds before stopping.

“Unimpressive now, but it’ll grow,” Ian said.

“What happens to the donor?”

“All neural networks—memories, knowledge, Interpreter, everything—are erased. Once a wipe has been made on a consenting candidate, they are considered legally dead.”

“‘Consenting,’” I said. “Is that real consent or prison consent?”

“We actually have a hefty waiting list. I’ve spoken to each donor myself. Many feel this is their chance at redemption. And, of course, their families get a comfortable sum of money and criminal records are erased.”

“I have schizophrenia,” Theresa said. I had almost forgotten she was there. “Well controlled; I haven’t had a flare-up in years. Would that mess with any of this?”

“Good point,” I said. She was engaging, which was encouraging. “We probably don’t want any of the schizophrenic donors, especially from prison. Should we edit it out, you think? Could be a dangerous window.”

“All our donors are serving life sentences, yes. And likely for violent crimes. But those with psychiatric issues are more likely to be victims of violence, not perpetrators, even in this population. That said, yes, we’d remove any identifiable brain diseases for both parties so as not to interfere with compatibility matching.”

“Does anything stay behind?” Theresa asked. “After the wipe?”

“No,” Ian said, a little too quickly. I sensed Theresa didn’t believe him. As the interpreter’s lines of codes rolled across the screen, I realized I didn’t either.

“Go,” Theresa said. “It’s Thursday night. Jerry and Ian won’t know what to do without you.”

“You remember Thursday nights?”

“Don’t change the subject. Get out of this apartment. You need it.”

My wife had seen a missed call from Ian on my phone. He was most likely at Jerry’s in Brooklyn, watching the Giants game.

“You sure?” I asked again. Thursday night drinks and football had been a pivotal tradition in getting me through the pre-Theresa chemo days. But I hadn’t seen them since before Theresa died. They’d have questions I wasn’t quite ready to answer.

“It’s hot outside,” Theresa said. She went to the kitchen and pulled out a can of cherry-flavored seltzer. “Drink plenty of water and walk slow.”

“What am I? Eighty?” But it was hot. I grabbed the can. “What will you do?”

“I’ll get out. Maybe I’ll find a ‘Was Black, Now White’ Meet-Up group. Joking, babe. I’ll probably pick up some wine for when you get home, so save some room.”

“Avoid that stuck-up place on Columbus. That lady puts you in a bad mood. Remember?”

“I can handle it. Now go. Give the boys my love.”

I took the crosstown bus to the 4 train to North Brooklyn and picked up a six-pack of Heinekens on the walk over to Jerry’s third-floor condo. He lived in a studio with his three-year-old cat.

A tall man twice my width opened Jerry’s door. We both paused.

“My man Ian,” I said. “It’s been a while.” My memory-lane sessions with Theresa had set my mind on seeing the Ian from college, back when he’d been a buck-fifty after dinner. He could eat anything without gaining a pound. Jerry and I called him the “black hole.” When the fantasy world of college melted away, we realized Ian was an alcoholic. Our journey to his sobriety led to us all becoming business partners. Off the poison, he gained what seemed like a hundred pounds in a year.

“You look like a new man!” Ian said. He slapped my outstretched hand away and brought me in for a hug.

“I feel like one.”

I looked around. Jerry was a lot like my wife; they both couldn’t stand a static environment. While Theresa never went more than a year without the itch to move, Jerry changed his condo’s skin like one changes clothes. Freshly painted red walls were decked with yellow-framed photos and his existential artwork that had found enough gallery homes to justify leaving his psychiatry practice.

“A new boyfriend?” I said, touching the wood of a hanging picture of Jerry and another man.

“Who knows?” Ian said.

“Old boyfriend,” Jerry said. Unlike Ian, he often approached unnoticed. A full head shorter than me, his small frame moved around a room without making a sound. He wore a homemade blue-and-white Giants jersey with a red-highlighted depiction of himself catching a football in the end-zone. “You’ve probably met him. He goes to our church.”

“Your church,” I said. Jerry had first come to Shiloh Church by my invitation. I never admitted that, at the time, I thought his love for men was pulling him to hell, and he never admitted that he only started going out of spite. In the end, God surprised us both. Homosexuality wasn’t the biggest threat to faith, after all. Cancer was.

As I sat on the couch centering the living room under a yellow chandelier, I ran my hands over the smooth fabric. Black bodies twirled over each other in a dance against the background of a fiery sunset that lit the length of the couch. Two fluff pillows made up the sun’s golden eyes.

“I know this piece,” I said. “Yours, right?”

“Yes, it is,” Jerry said.

“You never cease to amaze.”

Jerry handed me a beer. “Neither do you.”

“Theresa’s home, right?” Ian asked. Resurrection had gained notoriety shortly after that first introduction tour; Ian hadn’t blinked at the opportunity to sell and retire young. Working had never been his long-term plan. He remained on the company’s board but was more than happy spending his time traveling the world. “You got a picture?”

“I do, actually,” I said. I pulled out my phone. We’d snapped selfies her first night when neither of us knew quite what else to do.

Ian swiped his thumb one way then the other, and frowned. He looked up, back down at the picture, then back up at me. “You know this is a white woman, right?”

“Really?” I said. “She’s not albino?”

“They couldn’t find a sister? I would have found you a sister.”

“You hadn’t heard? The state only allows white donors. Keeps black bodies in prison.”

“You’re shitting me.”

“I am shitting you, actually,” I said. “Though I wouldn’t be surprised. Resurrection said it’s all about compatibility. Brain compatibility.”

“Who the hell told you that?” Ian imitated a balancing scale with his hands. “Black brain here. Black brain there. How doesn’t that add up?”

“It’s not about black or white. It’s about the wiring.”

“So, you’re saying Theresa has more of a white brain than a black brain?”

Jerry raised his hand. “Excuse me, I’m sorry, but what is a white brain?”

“Ask Theresa,” Ian said.

“Bottom line: whoever this woman is—was—her brain had just enough in common with Theresa’s for this to work,” I said.

“Question,” Ian said. “Would you let Theresa—this new Theresa—say ‘nigga’?”

“She doesn’t say it anyway.”

“Right, right. But what if she did?” When I didn’t answer, Ian took a step back to talk to both of us, his solid cheeks rising in a grin. “This is going to revolutionize the way white people justify using the n-word. ‘Well, my white friend who used to be black says it, so…’”

“A fitting legacy for you,” Jerry said.

“Fuck you.”

“Mm hmm. Who cares about white people using a word they invented, anyway? It’s just distraction from the real problem.”

“What’s the real problem?” I said.

“Nothing, D.” He took my empty can and stood. “I was just talking.”

“No. Speak your mind.”

Jerry looked to Ian, who held up his hands. “I’m not in this.”

“Really?” Jerry and I said together.

“I sold the company. Remember?”

“Whatever.” Jerry turned back to me. “Theresa…she’s dead. Dead, Darius. You don’t get to come back from that.”

“It’s no different from you hooking up a computer to someone’s brain to make the crazy go away,” I said. “It’s science.”

“It’s an abomination, that’s what it is. They made a copy of her. A copy. There’s a Theresa lying dead somewhere. Just because we didn’t have a funeral doesn’t make that less true. How do you even know the transfer worked? These prisoners, they’re resilient people. You think some simple brain-wipe could get rid of all of them? How would you ever know she’s just not acting like your wife?”

“I’d know.”

Jerry didn’t seem to hear me. He was pacing across his condo. He pointed to my phone. “That’s not Theresa. That’s a computer program that acts like Theresa.”

“Too far, bro,” Ian said. “Too far.”

“It’s time to update your beliefs.” I stepped forward. “Dead isn’t dead anymore, Jerry.”

“You can tell yourself that. But when you go home and look in her eyes, there’ll be no soul there. I know it and you know it.”

I turned to leave. Ian urged Jerry to come after me, but I knew he wouldn’t. Jerry and I would be good, we always were. Best friends knew when and where to walk away.

“Hey, D!” Ian called when I was halfway to the elevator. His breath was already heavy from the short distance he’d sprinted. “Jerry’s being an ass.”

“I know,” I said. I nodded to the beer he’d been nursing all night. “You good?”

“What? This? ELT keeps me in check. This is just my sweet tooth. Don’t worry about me.” He squeezed my shoulder. “How are you, bro?”

“Good. It’s tough without neurotech.” Just the mention of ELT had me craving the service. The anxiety melted away so easy. My finger outlined the remnant card through my pocket. “But the Xanax works. When I need it.”

“It’s probably for the best,” Ian said. “You don’t want to be confused when Theresa is confused. How is Theresa? Is she adjusting okay?”

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s like she never left.”

“I’m here if you need help with anything. I still have some connections. Keep me updated. We’re rooting for you two.”

Theresa was in the shower when I got home. Jerry’s ridiculous notion of trained, desperate inmates echoed loud enough to nearly push me into the bathroom. I needed to see her. Those eyes would calm me. I resisted.

I changed into shorts and a t-shirt and sat on the edge of the bed. A flash of light caught my eye. Theresa’s phone lit with a notification from the bedside table. My fingernails bit my palms. My teeth ground until it hurt.

“Fuck you, Jerry. You goddamn asshole.”

I snatched up the phone; she had a text message. From who? I tried my name as the password and, when that failed, considered my name plus my birthday digits, then stopped. Too many attempts and the system would wipe itself. I began to put the phone back when I noticed what had been beneath it. A hardcover book sported a female prisoner with both hands reaching from behind bars under the title: The Crisis of Women in the U.S. Prison System.

I touched the cover, wondered, and went back to the shower door. Faint whispers coated the sound of falling water. I waited, and listened, trying to make sense of it. Was that weeping?

The water trickled off; any other sounds died with it. Curtains opening. The flap of loose cloth. I imagined her drying off. The door opened. Theresa started.

“Jesus, Darius!” She turned to wipe the tears with her towel. “Are you trying to win the Creepster Award?”

“What happened?” I said.

“You scared the shit out of me, that’s what happened.” She pushed past and sat on the bed.

“You were crying. I heard it.”

Theresa mouthed a curse. “It’s nothing, babe. Really. I don’t want you to worry. Look, I got wine. We can play a game, watch a movie, quiz each other, whatever you like.”

“Talk to me first.”

She dried her hair in silence and stared at an old picture of us on the dresser. She bit her lip as her eyes welled. “I went to the Wine & Spirit store.”

I couldn’t help but smile a little. Was that all? The blonde middle-aged manager there had always been cold to us, as if we’d accidentally wandered into her high-class establishment while looking for a corner store to buy lottery scratch-off tickets. “That woman’ll mess up a wet dream on a good day. What did she say to you?”

Theresa shook her head. Her face leaked tears. “That’s the thing. She was nice. Nice! Showed me the new wines they just got from Italy and everything. As if I belonged there. She never tr-treated me like-like that when I was…“ She broke into sobs.

I pulled her close. She smelled fresh, like she always did out of the shower, but in a different way. “She’s an asshole, babe. Fuck her.”

“It’s not just that. It’s everything. I haven’t even been back to the school to see my kids.”

“We can go tomorrow, then,” I said. “Get your job back. You’ll teach. I’ll code. It’ll be like you never left.”

“Don’t you get it? I can’t ever go back. Those girls looked up to me. Now all I’d be telling them is they can grow up to be a white woman!” She shook her head as she turned to look at our picture. “I never knew you hated my skin.”

“What? Theresa, I—I didn’t have a choice. I swear. It was either this or…I just wanted you back.”

“I’m sorry. You’re right.” Theresa fingered my collar. “I’m scared, is all. I keep thinking you’ll fall out of love with me—this new me—and send me back.”

“Theresa, I would never. We have our second chance. That’s all that matters.”

She searched my eyes with hers. What lived behind those whites, now streaked with red?

I kissed her to drive the thoughts away, to stop my lips from asking about the phone or the book or when she would start being my Theresa again. When she kissed back, our mouths filled with salt and pain and fear.

We moved slow. Both of us were strangers to Theresa’s skin. I’d married her mind; the rest of her was something else. Our bodies didn’t mesh like they once had. I rammed her nose with my forehead as I positioned on top of her. She expelled me from inside her when she tried to squeeze me with her muscles. She burst into an infectious giggle in the middle of a kiss. I rolled to her side, laughing.

“We’re like teenagers,” she said. Moonlight through the window lit her face. “Old, stiff teenagers.”

“You’re going to love what I got, girl,” I joked as I slapped her ass. “You ain’t never had—”

At first I thought I had slipped off the edge of the bed and was laughing even as the back of my head hit the wall, sparking stars.

Laughter died. Theresa knelt on the bed, her salvaged eyes wide and twinkling even in the dark. Her hand danced with light, as if encased with diamonds. I blinked, and saw it was a sliver of moonlight on a long blade. I knew that reflection; I’d prayed to it almost every night during chemo, before Theresa. “Honey. Baby,” I said. “What is this?”

She stayed perfectly still. Had her body taken this stance before? A threatened inmate in a maximum-security prison, a different set of waves bouncing between her ears?

How different? a voice asked. It sounded like Jerry’s.

I rose, careful to keep the moonlit blade in my sight. I’d let it sit atop the kitchen counter as a reminder of how low things had gotten, how far I’d come. When was the last time I’d seen it? I didn’t remember it being so big.

I inched forward. Theresa was a statue. When I was close enough, I touched her shoulder. Her body trembled. I suppressed my fight or flight instincts, a response I was particularly geared towards. My mind knew this was my wife, that I loved her, but it was having a hard time reconciling knowledge with perception.

She tensed; for a terrible moment I thought she was going to attack. Our second chance at happily ever after, sliced down with the same dull blade from which Theresa had originally saved me. I responded by continuing forward. It’s all I had to combat the urge to run.

“You’re home,” I said. “You’re safe.”

All at once, her fire went away. She fell into me, sobbing. Her arm was limp at my side. The cold flat of the blade touched my stomach. I thought about gently taking it from her, but decided against it.

She continued to cry as we lay down on the bed, her body curved into mine. Her sobs carried her to sleep and, finally, silence. My arm numbed under her weight and my overextended neck had a painful crick, but I didn’t move. It was another hour before I slid free and gently pulled the knife from her dreaming fingers. I crawled out of the bed, went to the kitchen, and returned the blade to the holder’s open slot. I vomited in the sink and, when my stomach had nothing left, popped a Xanax.

I counted, meditated, traced the colored grooves in my remnant card as I waited for the benzo to do its job, and went back down the hall. Dark-bound whispers paused me at our bedroom door. I had heard these incoherent, private mutterings before, after Theresa’s cancer came back and she decided to go off all her medications, including the antipsychotics.

I pushed on the door to cause a creak; the whispering stopped. I let out my own: “Theresa?” Silence. Perhaps she was asleep. Perhaps I was the one hearing things. I climbed into bed, considered wrapping my arms around her, decided not to, and closed my eyes.

“I only want to know what happened,” I said. “What were you thinking? Why were you thinking it?”

“Can we just not talk about it? Please?”

The night had been strings of light sleep, broken by the same clenching thought: what the hell was I going to do with her? Her schizophrenia at its worst bore crippling paranoia, but never violence. Had this been from that? Or was that something deeper? Resurrection’s policy was clear: any psychiatric problems demanded reporting. But then what?

To the state of New York, Theresa was property. The original Theresa was dead and the donor inmate had essentially signed away her right to live. Until regulations on the rapidly evolving technology of neurocomputing arose, if Resurrection thought Theresa was a threat, their only obligation was to offer a refund. They’d get rid of her.

“I can’t fix this if I don’t know what the problem is.”

“Some things don’t need fixing,” she said.

“I’m a coder. Everything needs fixing.”

“That’s hilarious. Have you tried stand-up?”

“Do you think I want to hurt you?”

“No, babe, it’s not like that.”

“You’re hearing voices, then? Is it her? Is it the donor?”

“What? No!”

“Then who?”

Silence.

“I heard you whispering to them last night. Theresa would tell me.”

She slammed her fist against the coffee table. “I am Theresa!”

“Okay. Let’s just calm down,” I said, licking my lips. “You came at me with a knife. A knife. I saw the prison book. Did you have some type of memory? A flashback, maybe, from the prison?”

She looked at me, and I knew. Dammit, I thought, what am I going to do with you?

“I got freaked out,” she said. “That’s all. Can we just put this behind us?”

“Sure.”

Theresa leaned over and kissed me on the cheek. “Thank you. You want to rent a movie or something and stay in?”

“Yeah. Let’s just stay in forever. I bet you’d like that.” I stood. “I’ll be back.”

She looked like she was about to argue, but instead just said, “Don’t be too long, then. And remember to drink plenty of water and walk slow.”

Her words followed me out the apartment and sharpened in the New York humidity. Theresa would have fought. Theresa would have reminded me that I was her husband, not some boyfriend who could leave whenever things got hot.

Drink plenty of water and walk slow. She’d said that before. I Googled it as I entered Central Park, scrolled through several links purporting to have portraits of George W. Bush, movie quotes, and then tapped one. “Prison Maxims” stood bold over a list of phrases. One line read:

“Drink plenty of water and walk slow”: Time moves slowly, but there are consequences to every action.

I slowed, found a bench occupied with lazy pigeons, and sat. My thumb bit at my other fingers as I read over the phrase, again and again. I took off my jacket. My armpits were cold with sweat. I rubbed my pocket: flat. I’d forgotten my pills. I did, however, have my remnant card.

I called Jerry. It only rang once.

“It’s good to hear from you, D.”

“Schizophrenia,” I said. “How does it work? Is it in the body at all or just the brain? That’s a thing, right? The brain-body connection? Can’t you get depressed by having the wrong bacteria in your gut or something?”

“Whoa. Slow down. What’s the deal?”

“I just need to know how it works. Do the voices ever come from…somewhere else?”

“What. Happened?”

“I think Theresa’s hearing voices again.”

“There’s no reason to panic. She’s had that before.”

“No, you don’t understand. I think the voices are from her body. Her prison body.” I told him about the phrase and the search results. “She said it twice, Jerry. Twice.”

“Is everything else good between you two?”

“You think I’m being paranoid.”

“I think you can Google anything to make yourself believe what you want to believe.”

“I found her reading a book about prison.” I took a deep breath and closed my eyes. I knew how I sounded. I’d just gotten my wife back and I was worried about random phrases and her reading habits. “She came at me with a knife.”

I waited for the admonishment. I waited for Jerry to tell me there was only one thing left to do. I feared less the words and more what my reaction to them might be. That I might listen.

I opened my eyes. The sun was just dipping below the trees of the park.

“You tell Ian?” Jerry said.

“He’s still on the board and—”

“Say no more. Give me a second. There’s something I—just give me a second.”

I reached for my pills again, cursed, and ran my hands over my legs as if they were stained with my angst.

Onetwothree, onetwothree, one two three…

Jerry sighed. I sat up.

“I looked this up after Thursday,” he said. “I just had to know.”

“Know what?”

“I’ll just read it: ‘Cheryl McCarthy, Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women—McCarthy was convicted of killing Ricky “The Brick” Johnson, a heroin dealer, in July 2002. Johnson was stabbed nine times in the chest and the throat—’”

“Shit,” I said. “Nine times?”

“Yeah. ‘Authorities said McCarthy, who was known to have a long history of paranoid schizophrenia, killed Johnson and buried him in the woods. McCarthy’s attorneys said she suffered years of abuse under Johnson, who had used her paranoia to isolate her from family and friends, create financial and emotional dependence towards him, and force her into prostitution. The killing, they said, was in self-defense. The prosecutors argued her hiding the body suggested premeditation. What’s more, they made the case that she didn’t have a “true” schizophrenia. They pointed to a car accident in August 1997 that led to opioid and then heroin addiction. Her “schizophrenia,” they said, was substance-induced and a cause of her own negligence. McCarthy was sentenced to life in prison. She died in 2021 of unknown causes.”

“You’re sure that’s her?”

“Positive.”

“The voices,” I said. “It’s got to be this McCarthy woman.”

“That’s a reach, D. A big reach.”

“But it’s possible?”

“Anything is possible.”

“Can you think of a way?”

“Schizophrenia doesn’t hide out in the body. That’s absurd.”

“Forget that, then. Any way, at all?”

“Schizophrenia…it’s a whole brain disease. We used to think it was mainly specific neurotransmitters. Many people swore by the dopamine hypothesis, but it just didn’t explain what we were seeing on functional MRI. Hell, we even see changes in parts of the hippocampus—”

“The hippo-what? Jerry, you’re losing me.”

“The hippocampus is involved in memory. What I’m saying is, Resurrection’s wiping algorithm looks for well-studied neural networks. But if both donor and client had similar brain chemistry in overlooked portions of the brain…”

“That could leave a door wide open for McCarthy,” I said.

“Theoretically. Again, though, I don’t—”

“Could we erase it? I have her remnant card. Fix her, you know?”

“You don’t fix this, D. Theresa’s gone. You need to let her be gone. Look, have you been doing ELT?”

“Resurrection said—”

“‘You need to keep your mind clear,’ right? Is your mind clear, though?” Silence. “Look. One session and maybe you can start seeing things in a fresh light. Xanax is a shit medication. That ain’t going to cut it.”

“Got it. Thanks, Jerry.”

“Bro—”

“I got to go, bye.”

My phone vibrated as I walked across the park. I stopped in front of the 6 train, which would take me down to Brooklyn. I pulled out my phone, swiped through my apps without opening any, and then checked my messages. It was from Jerry: Stay woke, bro.

I frowned up at the two-story building. Its sleek, metal skin stood out like a healed thumb on a hand of sore fingers. The faded sign read Neurophoria. What an awful name. Ever since we’d founded Continuum, copycat neurotech clinics popped up all over the place. Whatever services they offered—electronic limbic treatment, memory manipulation, cognitive skills downloads—they all used the same neuro-network backup platform. All you needed was a remnant card.

A young woman with thick, purple glasses and neatly wrapped locs led me down rows of what looked like sleep-pods until we came to an open one.

“New design?” I said.

She shrugged. “I’ve been trying to get them to invest in the portable units. But what do I know?”

Portable ELT units were still years away, but I didn’t correct her. She’d have access to my brain soon, after all. She quickly ran through my medical and neurotech history and paused at the revelation that I’d had cancer.

“Any history of memory wipes?” she said.

“I wouldn’t remember, would I?”

I smiled. She was not amused. She reached for my ear. I recoiled. Tattooed on the back of my lobe was a hieroglyphic representation of all my neurotech. It was as intrusive as looking at my browser history.

“No memory wipes, okay? I guess you’re not into jokes?”

“Been a long day. If you had a memory wipe—”

“I know the risk. I’m good. Seriously.”

She considered me a moment longer, shrugged, and began to close the pod.

“No cap?” I asked.

“No need. Just lay your head back. You’ll know when you’re in the right place.”

“How—” But she was right. There was a click—not audible, but organic—as my body fell into an aural groove. Twin heat beams started at the base of my neck and drew lines up my scalp, bathing my head in a warm tingle.

Theresa filled my mind. My wife, strong and full, but not as she was now or as she had been before. She lingered there, an idea rather than a form, like the fragment of a dream. I struggled to hold on to her, for her face to form in my mind. The attempt sent my heart fluttering, sweat rolling down my face, and my fingernails in a rabid attack against one another.

“Relax.” The woman’s voice drifted into the pod, dream-like. “Every muscle in you is tense.”

I released them first; my mind followed. I let the anxiety flow out…

…and the memories flowed in.

Three years before Resurrection

When the cancer returned, it didn’t come for me.

The first time I missed one of Theresa’s appointments, I had a job interview with PlaySmart, a three-person start-up working out of the corner of a coffee shop. While I sat opposite a thirty-something woman in jeans and a hoodie worth millions, trying to pretend I wasn’t having a panic attack, unable to trust my hands to control the cup of organic brew she’d offered, worrying if she noticed the sweat on my forehead, or worse, cancer’s inscrutable shadow, Theresa was receiving the news that her CA-125 levels came back elevated. They’d have to do more tests. I returned her missed call after the interview.

“Bad news,” she said. I could hear the smile in her voice, and in some way that made it all worse.

“Are you at the doctor’s?” I said.

“At the school.” Her words crumbled at the edges. Rustling and static. When she spoke again, her voice was even. “How was the interview?”

“Terrible,” I said. “I’ll be there in ten.”

There were no tears that night. Somewhere deep we had known the cancer would come back for one if not both of us. That our time together was borrowed.

“I don’t want to do chemo again,” Theresa said. She’d gained her weight back. “If it’s bad…“

I touched her hand to let her know she didn’t have to say any more.

“I don’t want Resurrection, either.”

“Let’s get the results first.”

She pulled her hand away. “When Ma’s cancer came back, it was her brain. Near the end she’d look at me like she didn’t know who I was. Like she didn’t know who she was.”

“Theresa—”

“We need to be clear about these things now. I don’t want Resurrection.”

“You want to leave me, then?”

“No. Just the opposite. I want to be here with you, fully, until the end. We all have to go down this road. The Lord gives us only one shot at death; I want to do it right. Promise me, no Resurrection.”

“You don’t have brain cancer. These tests, they’re just to give the doctors something to do. But I promise. No Resurrection.”

I was wrong. Metastases to her lungs and brain. She cried at the news. I couldn’t cry. I was numb. Because I had made her a promise I knew I couldn’t keep.

Instead of chemo, we traveled. Spain. Norway. Japan. New Zealand. We left the medications—all of them—at home. The voices weren’t much of a bother when they first came trickling back. Whispering with them brought her a serenity I couldn’t. Sometimes she said it was God, reminding her He’d be at her side until the end. She stopped telling me about what she heard, and eventually I stopped asking. Towards the end of our world tour, however, her questions gave me a glimpse into her internal suffering. Do you think I’m going to hell? There’s no chance you caught your cancer from me, is there? Do you hate me because I’m choosing to die? When we came back stateside, sleep had completely abandoned her. She leaned to the left when she walked and often forgot to dress that side of her body. I couldn’t tell where the schizophrenia ended and the brain cancer began. When I found her sleeping in the empty tub because she thought her room was haunted, I convinced her to come with me to an ELT clinic. They created a remnant card.

The neurotech sessions quelled the voices. For a while, things were stable. We didn’t travel anymore. I inherited Theresa’s insomnia and spent countless nights staring at her remnant card.

A month before Theresa died I sat in Ian’s Resurrection office. I’d come alone. The office halls had wilted from a once excited vigor to abandoned silence, as if the company were Lazarus awaiting its own Messiah. Donors had jumped ship after multiple failed resurrections. Jerry thought their friend a fool for not selling back when things were hot. But Ian had always seen his babies through, to success or ruin.

“It was a good run,” Ian said. He poured himself a scotch, offered me a glass, and chuckled when he saw me looking at the clock. It was just before noon. “Don’t judge me, D. How’s Theresa?”

“Still dying.” I cut right to it. “Remember you said schizophrenia could cause a barrier to the connection needed for a successful neurotransfer?”

“Your professional voice.” He put his drink down. “I hate your professional voice. And here I thought you’d come by just to say hello.”

“Do you remember?”

“Vaguely.”

“What if it’s the opposite?” Ian had kept me abreast of Resurrection’s progress, and failures. They’d attempted almost two dozen neurotransfers. A few had gone terribly wrong; none had worked. “What if something like schizophrenia could create a stronger link?”

“You want my advice? Enjoy your wife, bro. One day she’ll be gone. Gone! And when you think back on her you don’t want it to be with regret.”

“That’s exactly what I’m trying to avoid. Humor me.”

Ian picked his drink back up. Sipped. Looked at me for a long time, then sighed. “Okay. I’ll humor you. For each patient and donor we look at millions of structural, environmental, and genetic markers. Beaucoup markers. You can’t get more compatible.”

“And yet it’s still not compatible enough.”

“Faulty logic there, D. Correlation isn’t causation. Likely compatibility isn’t the problem at all. Something else is. This isn’t rocket science. It’s harder than that.”

“What if your markers are too specific? Too rigid. You can have twin brains but vastly different outcomes.”

“Nature versus nurture. Biology one-oh-one.”

“But with something like schizophrenia, nature or nurture, it doesn’t matter. You know the end result is a fundamentally similar wiring. That Interpreter stuff you were spitting earlier, work that through the illness.”

“Schizophrenia is a spectrum. It really should be several different diseases. Two patients with schizophrenia could have ‘wiring’ as unique as fingerprints.”

“From what we know.” I sat forward. Ian’s belief that the human mind was science’s final frontier had pushed him into the field. I needed to tap into that wonder. “But what if there are core commonalities in areas we haven’t even discovered? Commonalities a strong deep learning algorithm could pick up on, easily. Tell me, when you’re searching for a donor, how many matches do you get? Out of a complete pool of inmates?”

“One, if I’m lucky.”

“If something like this works…“ I let my old friend finish the thought. He didn’t disappoint.

“Multiple matches. And multiple iterations, if need be. Shit. You son of a bitch.” Ian had risen to pace the barren office. When he turned back to me, the smile that had crept into his voice was gone. “She needs to be willing.”

I pulled out her remnant card. “She’s coming around. Full backup, plus regular neurotech sessions.”

“This is different.”

“She thinks it’s blasphemy, that she’ll go to hell.”

“There’s a lot of people who believe in hell, D.”

“Come on! She’s a paranoid schizophrenic; she’s not thinking right!”

“Jerry would trip if he heard you say that. Regardless, rejection is more likely if she’s not willing.”

“Can’t we just edit it? After the fact?”

The way Ian looked at me made me question a lot. My fingernail moved to scratch my palm. I swallowed the angst down and held his gaze. He had to know I was serious.

“I’ll have my engineer run sims on your theory. Attica State is trying to back out of our contract after all the bad media. A prison scared of a black man, ain’t that something? I’ve been in talks with Bedford Hills for women. This could be a new angle. I’ll work on that. You worry about Theresa. Get her in here, get her to consent, in person. If all that pans out—and that if’s bigger than the suite in hell we just reserved—I’ll consider it.”

“One more thing.”

“I’m afraid to ask. What is it?”

“Can we keep her eyes?”

“We have a full cosmetic team, but that’s way down the line.”

“No. Not recreate her eyes. Keep Theresa’s eyes. It’s…it’s important.”

“Yeah, D. Okay, yeah. Sure.”

The next time I took Theresa to her ELT appointment, she was too far gone to notice that the building was different. Convincing her that the cancer had erased the memory of agreeing to Resurrection’s insurance a long time ago was the hardest thing I’d ever done. But I did it, and when she entered the scanning machine she did it willingly. At least, that’s what I told myself.

“She looks like me,” Theresa said while holding up the photograph. Resurrection had secured a donor months ago, and discovering her features had become part of Theresa’s bedridden routine. I was starting to see the resemblance, too. The mahogany skin—without makeup and surprisingly smooth—full lips, sharp cheekbones, strong jaw, and short-curled hair. The death-row donor could have been a first or second cousin.

“She is you,” I said.

Before she died in home hospice, Theresa used her last breath to tell me something. I heard but didn’t listen. My mind was already on the future—our future. Ian’s crew came to retrieve the body and register it as part of the company’s research protocol. And then, we went to work.

Theresa had lost her hope. With Resurrection, I rediscovered mine.

I remembered everything.

I let the warmth of the Brooklyn sun solidify the memories. Starting Continuum fresh out of college. The cancer, selling the company, Ian starting Resurrection with his cut. Protecting Theresa from her stubbornness, her paranoia. Her initial resurrection. The initial joy. The return of the whispering voices that turned her against me. Working with Resurrection for a memory more conducive to happiness. For us both.

I called Ian.

“Bro! What’s good?”

“You’re still with Resurrection. You never left. Tell me I’m wrong.” I held my breath. The memories were there, but fickle, like a silhouette in the heat of summer. If I was wrong about this, I wouldn’t know what was right.

“How?” Ian said. His voice had changed. I gripped the phone.

“Neurophoria. Shitty place with a shitty name, but the neurotech works.”

“Shit, Darius. I told you not to.”

“Jerry suggested it.”

“Of course he did. That fucker. How much do you remember?”

“Everything, I think.” I shut my eyes against the pressure building behind my right temple. “How many times did we resurrect her?”

“Only two. And the second time was a favor. ‘Third time’s a charm’ ain’t going to fly with the board. I edited out my role in the company just so you couldn’t convince me again. Fucking Jerry. What. Happened?”

I took a second. I had to be careful. “Nothing. Nothing yet. She’s freaking out a little. She’s trying to find her identity.”

“Let’s bring her in.”

“You sound like Jerry.”

“I don’t like this, D. The other trials are going well. Theresa’s not an asset anymore. She’s a liability.”

“She’s my wife. And you wouldn’t have other trials if it weren’t for her.”

“Which is why I want you to bring her in. Before this ends badly.”

I stood there, feeling the rumble of many passing trains underfoot, thinking about what to do. The answer came to me sudden and clear, as if carried by the summer wind. Theresa wouldn’t like it, but it was for the best.

“You’re right. We need to fix this.”

“So you’ll bring her in?”

“No. Portable ELTs: are they out yet?”

“We’ve been equipped with those for months now. Why?”

“Could we do a reset in our apartment?”

“I told you there’s no third time. And even if I had a body to give, you expect me to drag it through your front door?”

“Not a new body, Ian. A new memory.”

Theresa came into the living room trailing energy. She wore her best red suit dress. It had been a week since she’d pulled a knife on me. Though it had stayed in its holder, the blade still hung between us. I slept on the couch in the living room and had fully replaced Xanax with neurotech clinic visits. My mind was sharp, clear. I closed the notebook I’d just finished and sat up.

“I know how to fix things,” she said.

“I’ve been thinking, too.”

“Just listen. Please.” When I nodded, she began to pace. “I’ve been feeling lost. Very lost. What’s my purpose? Why did God push me to change my mind and agree to this journey? Why did He bring me back like this? In this body? I think I’ve found out why. I talked to some people and if I take half a year of classes, I can be a prison social worker. I can really make a difference.”

She’d spit out the words faster than I could process them. She stood now in the middle of the room, breath heavy, a life in her eyes I hadn’t seen since before. But it wasn’t right.

“Where did this come from?” I said. “You never talked about prison before. Not once.”

“Every day I wake up and see another person’s face in the mirror. Even though she’s gone, even though I’ll never know who she really was, I still feel like I owe her something. Like her history is my history.”

“I’m glad you’re excited about something. And we can certainly consider it.”

“Consider?”

“I think something else might be better. I went by the school.”

Theresa shrank a few inches and dropped into the couch beside me. “You didn’t.”

“Those kids miss you. They understand why you haven’t been by. I talked to the principal. She thinks we can work something out. You can pick up with the girls right where you left off. This will help.”

I handed her the thick notebook I had compiled.

“What’s this?”

“It’s an album,” I said. “I went through all the meaningful pictures I could find and photoshopped you in. The real you.” I turned a page, excited. “See, this is you with your students. They saw it, and love it.”

“Darius…this isn’t the real me.”

“It can be.”

She continued to flip through the album while I tried to ignore her facial expressions. I held my breath as she came to the end. She pulled out a slip of paper that advertised the wonders of portable ELT.

“Brilliant, right?” I said. Sweat burned my face. My gaze flicked to the clock staining the wall. Ian would be here soon. “They agreed to change both our memories so that we remember you like this. It’s easier. And we can do it right here.”

“You fuck. You fucking fuck. You want me to forget who I was? Where I came from? I didn’t sign up for this.”

“When you look in the mirror you see someone who’s not you. Not black. Not Theresa.” I lifted her remnant card. “This will make it so you just see you. Don’t you want her gone?”

“No. I mean, I don’t know. She’s a part of me. Sometimes I feel her…”

“When you hear the voices?”

Her eyes flickered. “You wouldn’t understand.”

“Help me to.”

Theresa touched my face. Her hands chilled my skin. “I love you, Darius. I always have. I want this to work. I pray to God every day that you realize how much I want to just be here with you and love you.”

“Then do this for us.”

I held out the remnant card for her to hold and feel. She took it and hope crept into me. This would solve everything. Our perfect lives were just a—

She started, as if bitten.

“What is it?”

“Just my phone.” She reached into her pocket and turned towards the corner.

“Who is it?” I said, annoyed.

Instead of answering, she sat back on the bed. Her grip tensed around the phone and remnant card as one. Suddenly I regretted giving it to her.

“Theresa—”

“One second.”

Deep breath. In. Out. Patience. They were almost there. Onetwothree, onetwothree, one two three, one…two…three…

“When you said ‘it’s easier,’ what did you mean?”

“Huh?” I said.

“You said the memory reset would be ‘easier.’ Easier than what?”

“Nothing. I didn’t mean anything.”

“Easier than resetting me. Is that what you meant? If I don’t go along with this?”

“Babe, you’re sounding a little…well, paranoid.”

“Don’t you dare. Don’t you dare! I’m not some broken computer program. How many times have you reset me already?”

The room burned hot. Something had gone terribly wrong, terribly quick. The image of Theresa poised on the bed, ready to strike, flashed bright as the blade she’d wielded. I had to be careful; those hands had killed. “Who texted you?”

“How many, Darius?”

“Only once. It wasn’t a good fit. We both knew that.”

“I agreed to it?”

“Yes,” I said. “It was your idea.”

“Yeah?”

“It was.”

“Like going along with Resurrection was my idea? Or did you change that, too?”

“Where—where is all this coming from? Can I just see—”

I lunged for the phone. A mistake. Theresa whirled away, her arms tucked close to her body. In two quick strides she was at the door.

“Sorry. I’m sorry. I just want to talk. Me and you. Let’s slow down. Wait, where are you going?”

“To get rid of this thing. Once and for all.”

I followed my wife out into the hall. Her back was to me. She spoke rapidly with her hand to her ear as she went for the front door.

“Theresa!”

She broke into a run. I moved to intercept her. She cut to the right and turned as if to come towards me, a flash of light in her hand. The knife. Adrenaline sprang me forward; I pushed. Her balance easily broke. The edge of the carpet curled up and entangled her legs. I watched her fall in slow motion. I saw her forehead connect with the corner of the mantel before it happened.

Theresa rolled to the floor, screaming and bleeding. I rushed to help; she kicked me away.

“Stop it!” I yelled. “Stop it! You’re being unreasonable!”

I pinned her hands to the floor but she’d grown strong in her panic. I had to secure the knife. Her right hand yanked free, drove into my chest, and I lost my grip on the other. I desperately tried to gain back hold of them, wincing in anticipation of the unseen blade slicing into my body. If she would just calm down. If she would just be like Theresa. If she would just shut the fuck up for a second and listen to me and not those god-damn voices in her head.

Her screams stopped. Sharp pain on the back of my hands; her fingernails digging into the flesh. My own fingers were tight around her neck. I didn’t know how they got there. I’d let go as soon as she calmed down.

Onetwothree, onetwothree, one two three, one…two…three…

I released my grip and reeled back, as if the skin of her neck burned. Her eyes leaked pink, unformed tears; their lids hung halfway open. Splotches of red pressed into her neck as if invisible fingers continued to squeeze. Her lips were fuller than before, distorted and lopsided. Blood decorated the carpet around her head.

“Theresa?” I shook her shoulders. Gentle at first, then with rising panic. “Theresa, hey, baby, wake up.”

“What the hell, D?”

I turned to see Ian reeling towards us. He pushed me off Theresa and knelt beside her. His eyes grew as they took in everything. His mouth began to quiver.

“What did you do?”

“I was just trying to talk to her about our plan. She had a knife. She would have killed me.”

“This knife?” Ian handed me the cell phone.

“I swear she had one. She must have dropped it. You should have seen her, Ian. Is she…?”

“She’s breathing.” Ian’s fingers against her neck beneath the jaw. He tilted her head to the side. An unseen gash gushed dark blood from her head. “D…”

“She fell. I swear she did. I didn’t do that.”

“And this? Did her neck fall into your fingers?”

“I just wanted her to listen. I wasn’t trying to hurt her. She was hysterical!”

“I wonder why?” The way he said it told me he wasn’t wondering in the same way I was.

I started: Theresa’s phone. I looked down at the vibrating metal, at first bemused by the green envelope blinking on the screen. A text message, from a private number. I thought, typed in a password, and grunted. After three failed attempts, the phone told me that security had cleared the device of all information.

I could see her breathing now. Slow and shallow, but there. The knowledge that she was alive dissipated some of the panic. This woman wasn’t Theresa. Only the shell of a prisoner that Theresa had tried to inhabit. Tried, and failed.

“The voices came back,” I said, as if that explained everything. “Strong, like last time.”

“The voices didn’t strangle her. You did.”

“The schizophrenia link might have not been the best idea. She wanted to be a prison social worker. That’s not Theresa.”

“Prison social worker sounds pretty fucking good to me, voices or not. Would have made for a hell of a PR.”

“We’re a good team. We just have to find the right match.”

Ian sat down beside me. He wiped his mouth. A wave of alcohol hit my nose, then was gone. “Things are different, D. Resurrection just signed contracts with three state prisons. We can’t afford a mess right now. And this…this is a fucking mess. If it came out we covered something like this up…” Ian stood. “I have to call the police.”

“Over property?”

Ian recoiled, as if I had just spat in his face. He went into the kitchen and leaned over the sink. Then he began to laugh. When he came back, he was holding a chef’s blade. The chef’s blade. He handed it to me, handle first.

“This what she came at you with? It was in the holder. Property or not, you’re a black man and this is a white woman.” Ian turned to look at Theresa as if to confirm that this was indeed true. “Fuck. I—I have to think about the company, D.”

“You’re just going to throw me under the bus, then?”

“I gave you your second chance. You told me Theresa was the problem and I listened. That’s on me. But this fuckery? That’s on you.”

“Resurrect us both, then,” I said. I held out my remnant card along with Theresa’s. “New contract, new opportunities, right?”

“Even if I could, how would I justify—”

“We have to try! Take them, please. If the police get mine they’ll lock it away. Please.”

Ian hesitated, then took them. Regretful eyes flicked to the knife. “I can’t transplant someone who’s still alive.”

“Let me worry about that,” I said. “You’ll make it work. You can clean up anything.”

His mouth went hard. The decision about whether or not to wrestle the knife away jumped between his eyes. Part of me wanted him to take it. The part of me that hated what I’d done to Theresa.

But that part was weak. That part could never do what was needed to make things right again. Could never have gotten us this far.

“This can’t be her last memory of me,” I said. “Please, Ian.”

Ian cursed, low and fierce, then walked down the hall punching at his cell phone.

“Hi, yes. I need someone to check on my friend right away.” Ian gave my address. “He called me, upset, said he was going to kill himself. I asked to talk to his wife and he started crying, wouldn’t tell me what happened. They’ve had problems. Bad problems, but I thought things were getting better. I’m worried he…please, can you just check on them? I’m heading over there now. Yes, please, oh thank God. I’ll be out front. Tall, black, two hundred fifty pounds. Unarmed.”

Alone again, I went to open the curtains. Yes, the moon; full and bright. Its milky blessing bathed the room. Now I could do what needed to be done. As I assumed my final position, the significance of the cold blade against my skin wasn’t lost on me. Though she had never known it, Theresa had saved me from it before. Here she was, saving me again, but by leading me towards instead of away. The blade had always been consistent in its offering of control. Before, that meant avoiding a hopeless future. Now, it would usher me—us—into a bright, new one.

I gave you your second chance. Would Ian resurrect them both? He had to. It was the only option. The current narrative wasn’t right. “Man forces wife to cheat death, then kills her in a panic”? What if her body survived and remembered him that way? Made him part of her “overcoming adversity” Resurrection PR story? That wasn’t me. I—we—could do better.

I sat there, under the moon. Sirens lifted from somewhere in the distance. I looked down at the prisoner’s body, which was starting to stir. What had Theresa told me about death? You jump and feel yourself going down, and down, and then you come back up.

Could I take that leap?

Buy the Book

The Perfection of Theresa Watkins

“The Perfection of Theresa Watkins” copyright © 2020 by Justin C. Key

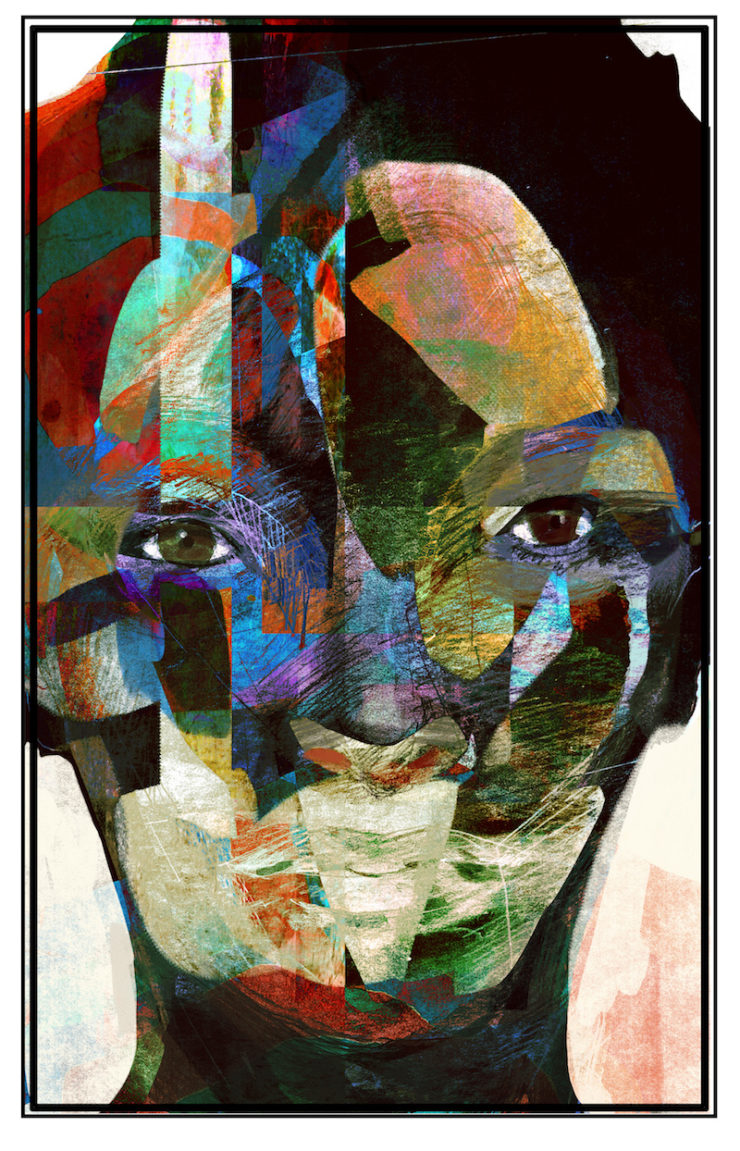

Artwork copyright © 2020 by Eli Minaya